Ulster Linen Workers

Ewart's Linen Factory, Belfast

From Flickr Commons via Wikimedia Common

deemed to be in the public domain

Please scroll down for the stories.

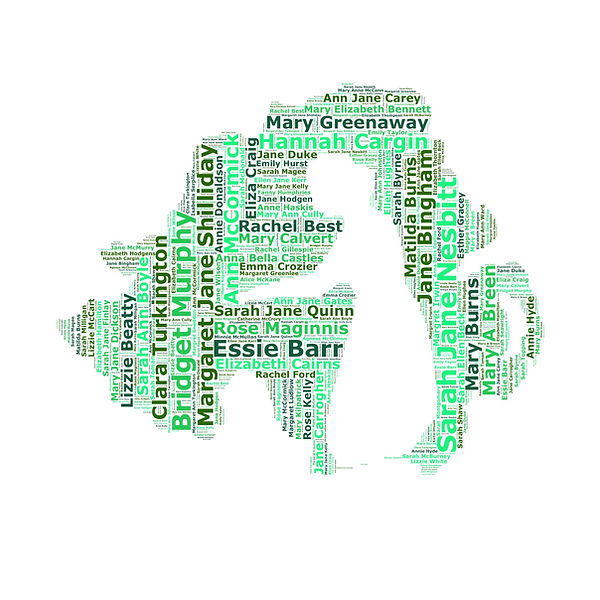

For the Forgotten Women Friday held on 17 October 2025, the focus was on women who were working in the linen industry in Ulster at the time of the 1901 Census. Specifically, women between twenty-six and thirty-six years of age working in the spinning mills, weaving factories, linen manufacturers and hemstitching factories of the linen trade in Counties Armagh and Down, in what has been Northern Ireland, since 1921. We have also included some hemstitchers who lived in rural areas and worked at home, getting piece work through a local Hemstitching Agent.

Linen has been produced on the island of Ireland at least since Tudor times. The Industrial Revolution, as well as transforming the linen industry in Ulster, also changed how and where people lived and worked. Mills and weaving factories sprung up over Belfast and surrounding towns and villages, and many people poured into these areas from the countryside looking for work. These people who moved from rural areas to urban areas soon discovered that working in the weaving factories and spinning mills was very different to producing linen at home, which had been the way in the past. In Ulster, the linen industry grew to the point where in 1900 there were 35,000 power looms operating, while in Great Britain and Europe there were just 22,000 in total.

Whole families often worked in a mill. The Factories Act of 1874 increased the starting age for children from 8 years to 10 years old. Children were employed as ‘half-timers’ who went to school half the week and worked in the mill the other half. Up to three quarters of the workers who were employed by the factories and mills were women and children. This was mainly because they were cheaper to employ. However, poverty was rife and so sometimes the age of the children was lied about so they could enter the mill at an earlier age and begin contributing to the household income.

In the late 1800s, the typical working day began at 6am and ended at 6pm. If you were late in the morning, you could be locked outside, fined and have your name entered into a complaints ledger. The hot, dusty, noisy and moist environment of the wet and dry spinning rooms made life very unpleasant. Three quarters of an hour was allowed for breakfast at 8.15am, and the same time allowed for lunch. The weekly wage for spinners, predominantly a female profession, was around 7 shillings and sixpence. Roughers and Sorters, mainly male jobs, received around 17 shillings and sixpence and 22 shillings and sixpence respectively. Tuberculosis often spread quickly through the mills and factories, killing both young and older workers; as a result, life expectancy for people in the linen industry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was quite low.

The 1908 Belfast Health Commission report described an improvement in working conditions with the installation of fans to draw away flax dust, as well as improvements to ventilation. However, working conditions in the linen mills were of serious concern and detrimental to health into the late 20th century.

In 1910, the Weekly Irish Times described infant mortality rates as being very high and attributed this to the number of ‘premature births amongst women working in the mills and factories’ who often had to work up to the beginning of their confinement. A women often returned to work quickly after giving birth, ultimately because the wages were necessary for her family to survive.

The dataset of women for this research has been compiled from the 1901 Ireland Census, which is freely available online at www.census.nationalarchives.ie. The information given to researchers for each woman will include her name, townland or street address, the county (Armagh or Down), the DED (District Electoral Division) and her age, birthplace, occupation and religion. This should enable easy identification of each woman on the 1901 census and in other online documentation. Volunteers will also receive a document called “A Guide to Online Northern Ireland Family History Research”, which will tell you which websites to use, and give some guidance on what they offer and how to use them.

The women who worked as weavers may have just been described as linen weavers, but in some cases they were described as damask weavers, cambric weavers or diaper weavers. Damask linen is the highest quality of linen cloth. Cambric is a very fine linen, of the type used for handkerchiefs. The word “diaper” actually refers to a weaving technique used since medieval times in which the threads are woven in a way that produces a pattern within plain white cloth - often a diamond pattern. For centuries, household items such as table cloths and napkins would often be made from plain “diapered” linen.

The jobs carried out by the women are explained below:

Preparer

Working in the preparing room of the mill where flax was prepared was described by one mill manager in 1875 as being ‘sure death’. The process of preparing the flax and also hackling, which is the process of splitting the flax fibres, created a huge amount of flax dust or ‘pouce’. These rooms in the mill were badly ventilated and so the workers were almost constantly inhaling this dust. It dried out the throat, caused a cough and led to chest illnesses such as byssinosis. Those suffering from byssinosis would often have a cough, fever, shivers, fatigue, and their lungs would usually be permanently affected.

Spinner

Spun the flax into linen yarn. The spinning rooms where the flax was spun to create yarn were wet and hot. This was to stop the flax from breaking, but these working conditions deeply impacted the spinners. They worked in their bare feet in attempts to stay cool, but the floor was always wet and so we see spinners suffering from what they describe as toe or foot rot. ‘Onychia’, where the nail bed becomes infected and ultimately the nail is lost, and also ‘deformity of the foot’ was prevalent amongst the people working in the spinning departments. The spinners also worked with hot water which caused a skin condition on the face and arms, or any skin uncovered that was touched by flax water. In the hot and humid conditions, it might be unsurprising that spinners often fainted and this was sometimes attributed to anaemia. The young girls and women employed in the mill became skilled lip readers in order to communicate over the noise.

Warp Winder

Wound the warp threads into place on the loom before the weaving process can begin. Then the shuttle wove the weft threads in between, creating the cloth. The warp thread runs continuously down the length of the cloth, while the weft thread runs across the width of the cloth.

Winder or Bobbin Winder

Wound the yarn from cones of linen yarn onto either weaving ‘pirns’ or bobbins for insertion in the shuttle, which goes back and forth across the loom to create the linen cloth, when weaved in with the warp threads.

A boat shuttle with a pirn A boat shuttle with a bobbin

Images thanks to Kelly Casanova Weaving Lessons - used with permission

Reeler or Yarn Reeler

Operated a machine that could wind the yarn onto the bobbin.

Weaver or Power Loom Weaver

Wove the linen cloth using power looms, which came with its own set of possible and likely illnesses. This was a warm, damp and badly ventilated room in the mill and we see weavers suffering from chest problems like bronchitis.

Sweeper

Swept the floors of the mills – very dusty work and bad for the lungs.

Hemstitcher

Hemstitching is a decorative drawn thread work or openwork hand-sewing technique for embellishing the hem of clothing or household linens. In hemstitching, one or more threads are drawn out of the fabric parallel and next to the turned hem, and stitches bundle the remaining threads in a variety of decorative patterns while securing the hem in place. Multiple rows of drawn thread work may be used. Hand hemstitching can be imitated by a hemstitching machine which has a piercer that pierces holes into the fabric and two separate needles that sew the hole open.

Hemstitched handkerchiefs

Image in the public domain from Wikimedia Commons

Useful and interesting articles on the linen mills may be found in the British Newspaper Archive, such as Hayes & Co Spinning Mill, Seapatrick, Banbridge; Sinton & Co Spinning Mill, Tandragee; W Liddell & Co, Linen Manufacturers, Donacloney; Dunbar McMaster & Co, Gilford Mill; Murphy & Stevenson, Dromore.

1901 Dromore Street Directory mentions J.R. Minnis, Linen Manufacturer, and there is also a hemstitching factory and a cambric handkerchief factory.

There were many spinning mills, weaving mills, linen manufacturers and hemstitching businesses in larger towns such as Lurgan and Portadown, so it’s hard to know in these cases where an individual might have been employed.

1901 Lurgan Street Directory: “Among the industrial centres in Lurgan in 1901 are the extensive power-loom weaving factories of Mr. James Malcolm, D.L.; the Lurgan Weaving Company, Ltd.; Messrs. Johnston, Allen, & Co.; and the manufacturing concerns of Messrs. Robert Watson & Sons, John Douglas & Son, Samuel A. Bell & Co.; Mathers & Bunting, John Ross & Co.; James Clendinning & Sons; Richardson, Sons, & Owden; John S. Brown & Sons, Joseph Murphy & Co.; and the hemstitching factories of the Lurgan Hemming and Veining Company, John Ross & Co., Faloon & Co., James B. Hanna, J. Maxwell & Co., Murphy & Stevenson, Mercer & Brown, James Clendinning & Sons, Johnston, Allen, & Co.; Searight & Co., and Mathers & Bunting.”

1901 Portadown Street Directory: “The manufacture of linen and cambric is extensively carried on. There are nine large weaving factories and a spinning mill, which gives employment to many people; and several hemstitching factories. These included Achesons, Ltd., linen manufacturers, Bann View Factory; Atkinson, Joseph, grocer and linen manufacturer, Corcrain; Castleisland Weaving Factory; Dawson, Thomas, J.P., yarn merchant and linen manufacturer, Corcrain House; Graham, David, & Co., spinning mills, Castle Street; Greaves, O. V., Weaving Factory, Annagh; Lutton, A. J., & Sons, linen manufacturers, Edenderry; Reid & Son, linen manufacturers and yarn dealers, Tarson; Robb, Hamilton, steam power weaving factory; Sinton, Thomas, linen manufacturer, Market Street and Laurelvale; Spence, Bryson & Co., weaving factory, Portmore Street; Tavanagh Weaving Factory; Watson, Armstrong, & Co., power loom weavers, Watson Street; Watson, James, linen manufacturer, Devon Lodge; Wilson, J. Loftus, Ashgrove House, linen manufacturer, works, River Lane; Wilson, S. & Co., linen manufacturers, West Street.”

Further Reading

-

https://www.craigavonhistoricalsociety.org.uk/rev/luttonlinentrade.php

-

https://www.ulsterarchitecturalheritage.org.uk/case-studies/gilford-mill-dunbar-mcmaster/

-

https://craigavonhistoricalsociety.org.uk/rev/luttonindupperbann.php

-

https://www.archiseek.com/1866-liddell-mill-donaghcloney-co-down/

-

https://www.poyntzpass.co.uk/uploads/Sintons_Mills_Tandragee.pdf

Martha Barron, later Martha Maginnis 1874-?, from Bessbrook, Co. Armagh - Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Rachel Bates 1868-1918, from Mullaghbrack, Co. Armagh - Emigration, Illegitimacy, Mental Health, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 8 minute read.

Sarah Ellen Beck 1867-1916, from Drumillar, Co. Down – Lawbreaking, No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 5 minute read.

Mary Elizabeth Bennett, later Mary Elizabeth Lauder 1870-1925, from Tullyhugh, Co. Armagh - Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Jane Bingham, later Jane McDowell 1870-1938, from Ballyroney, Co. Down – No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.

Catherine Brady, later Catherine McCrory c.1873-1901, Markethill, Co. Armagh – Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.

Mary Ann Breen c.1871-? , from Derrytrasna, Co. Armagh - No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 5 minute read.

Hannah Cargin, later Hannah Caldwell 1874-1942, from Ballykeel, Dromore, Co Down, Ireland – Emigration, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.

Anna Bella Castles 1869-1942, from Derrytagh, Co. Armagh – Emigration, No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 9 minute read.

Mary Jane Dickson c.1867-1935, from Drumadonnell, Co. Down – No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 9 minute read.

Sarah Domigan, later Sarah Topping afterwards Sarah Caves 1866-1932, from Donacloney, Co. Down – Sickness, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.

Annie Donaldson, later Annie Curran 1869-1929, from Gilford, Co. Down – Women at Work, Linen Industry. 8 minute read.

Sarah Doyle, later Sarah Byrne 1870-?, from Banbridge, Co. Down – No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.

Mary Dynes, later Mary McCormack 1869-1941, from Edenderry, Co. Armagh - Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.

Rachel Gillespie 1867-1941, from Knocknamuckley, Co. Armagh – Emigration, No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read

Margaret Ann Graham, later Margaret Ann Clarke 1865-1902, from Killevy, Co. Armagh - Women at Work, Linen Industry. 8 minute read.

Matilda Hadden, later Matilda Burns 1872-1953, from Lisdrumchor, Co. Armagh – Accident, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Isabella Hamilton, later Serplice 1867-1921, from Magheralin, Co. Down - Women at Work, Linen Industry. 15 minute read

Anne Haskis, later Anne McDowell 1864-1919, from Edenballycoggill, Co. Down – No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Elizabeth Hodgen 1866-1947, from BallyMcCormick, Co. Down - No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 7 minute read.

Emily aka Emma Hollywood, later Emily aka Emma Crozier 1866-1956, from Portadown, Co. Armagh - Women at Work, Linen Industry. 9 minute read.

Ellen Jane Kerr 1873-1911, from Ballynabragget, Co. Down - No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 2 minute read.

Emily Lowden, later Emily Hurst 1867-1936, from Lurgan, Co. Armagh – Emigration, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Margaret Ludlow, later Margaret Holland 1869-1938, from Derrycrew, Co. Armagh – Child Mortality, No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.

Jeannie MacLean, later Jeannie Davidson 1866-1906, from Bessbrook, Co. Armagh – No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 5 minute read.

Sarah Magee, later Sarah Carroll 1868-?, from Magheralin, Co. Down – No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 2 minute read.

Rose Anne Maginnis 1867-1956, from Greenan, Co. Down– No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Sarah Jane Mallard, later Sarah Jane Lackey 1871-1928, from Edenballycoggill, Co. Down – No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.

Lizzie McCart 1866-1918, from Derlett, Co. Armagh – No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 11 minute read.

Mary Elizabeth aka Elizabeth Mary McComb 1869-?, from Bessbrook, Co. Armagh - Women at Work, Linen Industry. 10 minute read.

Mary Ann McGauhey, later Mary Ann Johnston 1868-?, from Lisnagat, Co. Armagh – Women at Work, Linen Industry. 6 minute read.

Rachel McKee, later Rachel Ford 1869-1945, from Derryhale, Co. Armagh - Emigration, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 10 minute read.

Sarah McKeown, later Sarah Toman 1869- 1939, from Ballymacanallan, Co. Down – Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Jane McKinney, later Jane Wilson 1872-1942, from Derryinver, Co. Armagh – Emigration, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.

Sarah Montgomery 1870-1903, from Dromore, Co. Down – Disability, No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.

Alice Murray, later Alice McKane 1867-1907, from Seapatrick, Co. Down - Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Margaret Nicholson, Later Margaret Irwin 1870-1909, from Derryane, Co. Armagh – Women at Work, Linen Industry. 2 minute read.

Mary Robinson, later Mary Calvert 1869-1956, from Clare, Co. Down – Women at Work, Linen Industry. 13 minute read.

Martha Ross 1862-?, from Tassagh, Co. Armagh - Women at Work, Linen Industry. 7 minute read.

Sarah Jane Scott, later Sarah Jane Laverty c.1872-1912, from Portadown, Co. Armagh – Accident, Child Mortality, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Margaret Jane Shilliady, later Margaret Jane McCully 1873-1935, from Cloghskelt, Co. Down - Emigration, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 10 minute read.

Margaret Sneddon, later Margaret Adamson 1875-1952, from Banbridge Co. Down – Emigration, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 17 minute read.

Emily Taylor, later Emily Lyons 1871-1918, from Lenaderg, Co. Down – Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Elizabeth Toner, later Elizabeth Joyce 1867-?, from Loughgilly, Co. Armagh – Women at Work, Linen Industry. 6 minute read.

Margaret Ann Turkington 1867-1938, from Charlestown, Co. Armagh – No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 4 minute read.

Lizzie White c.1872-1924, from Gilford, Co. Down – No Descendants, Women at Work, Linen Industry. 3 minute read.